|

Online

Archive

|

| Issue 8 - November 1972 |

| Taoist Art |

The

Chinese Taoist Art Exhibition in the Gulbenkian Museum in Durham, which

opened in July, has been well received by a considerably wide section

of the public. Due to its success, this pioneering exhibition is to remain

on show until the end of the year in the Museum's pitifully small temporary

exhibition room. But you do feel that the size of the exhibition room

is immaterial for the understanding of the workings of Taoist ideas in

Chinese art. In fact, one is reminded now and again that there is a world

beyond the walls of that exhibition room, and beyond the primarily visual

impact of this interesting display of over 250 choice items. You travel

freely between Heaven and Earth, and scale the Universe with the freedom

of the Elements of Nature, and the penetration of the strength of your

own mind. The

Chinese Taoist Art Exhibition in the Gulbenkian Museum in Durham, which

opened in July, has been well received by a considerably wide section

of the public. Due to its success, this pioneering exhibition is to remain

on show until the end of the year in the Museum's pitifully small temporary

exhibition room. But you do feel that the size of the exhibition room

is immaterial for the understanding of the workings of Taoist ideas in

Chinese art. In fact, one is reminded now and again that there is a world

beyond the walls of that exhibition room, and beyond the primarily visual

impact of this interesting display of over 250 choice items. You travel

freely between Heaven and Earth, and scale the Universe with the freedom

of the Elements of Nature, and the penetration of the strength of your

own mind.

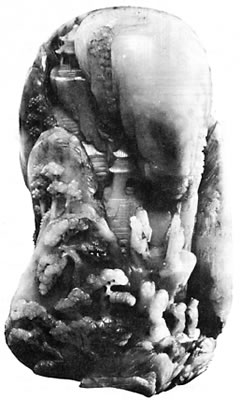

The visitor is invited for the first time to take a more profound approach to Chinese art, and try to come to terms with the initiated Taoist interpretation of these works of art, in which, for example, a kidney-shaped carved jade is symbolic of the vulva and a tripod vessel of the penis. On the other hand one is also reminded that the initiated interpretation of sexual intercourse (with all its realistic representation) is not considered erotic at all, but deeply religious and philosophical. We see the workings of Taoism in Chinese art, the open philosophical system of Taoism that reconciles opposites, and fuses the yin and yang elements of Nature, in order to emphasise the Harmony of the Universe. (It is in this context that the sexual act becomes so significant.) One also learns the Taoist art of active participation in the discovery of the mysterious forces of the Universe, frequently by viewing things on a miniature scale. The splendid conglomeration of Chinese folklore, nature-worship and metaphysics is shown in ten main sections that range from the symbolism of shapes and colours to occult arts and sexology.

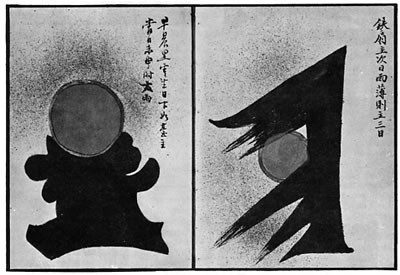

Through these sections we are shown the development of abstract tendencies

in Chinese art, e.g. in the compositional and symbolic development of

Taoist calligraphy, and particularly in landscape painting, which represents

one of the highest levels of abstraction from outward reality that the

Chinese genius has been able to achieve. The exhibition |